SSWR DSC Monitor: October/November 2025

This issue highlights how doctoral scholars are learning to live, work, and create in a digital era, embracing AI and emerging tools while striving to stay grounded, balanced, and true to their scholarly values.

Editoral

Jennifer Elliott (She/Her) & Sadaf Sedaghatshoar (She/Her)

Image depicts black wifi symbol etched onto stainless steel. The steel is brushed metal and there are drops of water on the surface.

As the semester unfolds, many of us find ourselves navigating a rapidly evolving academic world—one shaped by constant innovation, endless screen time, and new questions about how technology intersects with our work and well-being. The challenges we face as doctoral students go far beyond research deadlines; they touch every part of our daily lives. Between learning to use AI responsibly, managing digital fatigue, and preserving space for reflection, we’re continually redefining what it means to grow and thrive as scholars.

This issue of the SSWR Doctoral Student Committee Newsletter centers on the ongoing process of adaptation. Each article explores how technology shapes the way we teach, write, and connect, while reminding us that progress must also include care for our ideas, our communities, and ourselves.

Doctoral life in 2025 is demanding, but it’s also full of possibilities. As social work scholars, we have the opportunity to model intentionality—to engage with technology thoughtfully to protect our boundaries, and to lead with integrity in a world that rarely pauses. May this issue encourage you to reflect, recharge, and recommit to the balance that sustains both your scholarship and your humanity.

Thank you for being part of this growing community of thinkers, advocates, and change agents. We hope this issue inspires you to pause, reflect, and reconnect with the values that guide our profession: justice, balance, and humanity, as we continue navigating an ever-evolving digital landscape.

This issue includes

AI in the Classroom by Kevin Yu (He/him) & Yujeong Chang (She/Her)

Navigating Connection and Coping in a Digitally-Driven Academic World by Marsha McDowell (She/Her)

Tech Burnout and Boundaries: Surviving Always-Online PhD Work by Ruijie Ma (She/Her)

The Uncertainty of Academic Freedom by Leah Munroe (She/Her)

Doctoral Student Spotlights: Celebrating Doctoral Students’ Accomplishments

AI in the Classroom

Kevin Yu (He/Him) & Yujeong Chang (She/Her)

Image Description:

Image depicts an empty college classroom. There are three rows of light wooden tables with two chairs at each. There is a white board, a monitor, and a darkened window at the front of the room.

AI In The Classroom

The Student Perspective

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become part of daily life in higher education much faster than most of us expected. As doctoral students, many of us are figuring out how to engage with it in ways that support our work without compromising the core values that guide our scholarship. At the same time, many questions remain. Are we truly comfortable using it? Where do we draw the line between support and dependence? Is this still our work if AI had a role in shaping it? These questions surface often, and there are no simple answers. What feels clear is that we are unlikely to return to a world without AI. The challenge now lies in learning how to live, learn, and create within this new reality.

For me, the most honest way to describe my approach is simple: I do not fully trust AI. I have seen it produce incorrect information on many occasions, and I cannot rely on it without extra careful checking (sometimes it feels like it’s more work than not using AI). As a result, when I use AI to summarize or synthesize information, I verify every detail. I never use AI for citations, because fabricated references are common. This means AI is not a tool I can hand work over to; it requires close human supervision.

Still, there are times when AI is useful. I often use it to help with coding and debugging in statistical software such as R or Stata. However, I run each line of code to ensure the AI-generated output performs as intended and achieves the desired result. I sometimes ask AI to explain complex concepts in plain language and simpler terms, which can help me understand them more quickly. I also use it for brainstorming ideas, such as potential titles or section headings, when I feel stuck. For grammar checking and editing, I prefer Grammarly as an AI tool, as it tends to be more reliable.

Because I know how easily AI can make mistakes, I also consider honesty as a central issue in both collaborative and academic work. Being transparent about whether and how we use AI matters. Whether I am writing a paper, preparing a presentation, or completing a class assignment, I believe it is important to clearly acknowledge where AI was used, for what purpose, and how its output was verified. This helps build trust with professors, peers, and within our broader scholarly community.

In collaborative projects, establishing clear expectations regarding AI use can be especially helpful. Before starting a collaborative project, I find it useful to have an open discussion with collaborators about how, when, and to what extent we are comfortable using AI. Laying this groundwork early can prevent misunderstandings later and ensure that everyone is on the same page about AI usage.

Beyond ethics and collaboration, equity and access are also important considerations. AI can support students by helping with writing, language translation, or accessibility needs. But access to the most advanced tools often requires payment, and institutions differ in the level of support they provide. This can widen existing gaps. Bias is another major concern in AI in education. AI systems are built on existing data, and that data often reflects social inequalities. As social work scholars, we need to stay aware of how these biases might affect our work and continue to approach AI critically.

The growing use of AI also raises questions about the purpose of learning. If information is easily generated, what does it mean to know something? If AI can draft text quickly, what is the value of our own contributions, and how do we define it? I believe our role as scholars is not to produce content as fast as possible but to exercise judgment, such as to ask meaningful questions, evaluate evidence carefully, and decide when and how AI should be used.

We also cannot ignore the reality that AI is now part of the academic environment. It is being used to design course activities, develop syllabi, and support instruction. While some of these uses may be helpful, caution is still necessary. The principle I try to follow is straightforward: do not trust AI unconditionally. Always check, re-check, and confirm before using any AI-generated information in academic work.

Most students I speak with do not see AI as something to either fully embrace or completely reject. Many of us see it as a tool that can support learning if used carefully. For me, that means documenting when and how I use it and taking the responsibility for the quality and accuracy of my work, regardless of what tools I use.

AI is not going away, and our task is not to decide whether it should exist but to decide how we will interact with it. A cautious, critical, and transparent approach will allow us to benefit from its potential while maintaining the standards that define doctoral scholarship.

The Professor’s Perspective

The response to artificial intelligence (AI) tools in higher education has been wide-ranging. On one end of the spectrum, there are universities like Ohio State University, which have encouraged faculty and students to integrate AI into their teaching and learning. On the other hand, institutions like Sciences Po in Paris have outright banned the use of AI in education. For most institutions, including mine, there are no clear guidelines regarding AI use, leaving much room for interpretation among faculty.

I have been in classrooms where AI is treated as the enemy. These professors explicitly prohibit the use of AI tools in any assignments in their classes. They cite reasons such as the breakdown of creative thinking, destruction of natural resources, and invasion of intellectual property, all of which I agree with. AI can remove the creative element from learning entirely, defeating the purpose of higher education. Moreover, the resources required to power AI, such as water and electricity, are also immense. The growth of AI is displacing workers and causing real harm, and exacerbating inequities to vulnerable communities. Lastly, the foundation of AI itself is ethically questionable, as it often utilizes and repurposes people’s content without their consent.

Some professors take a more moderate stance toward AI. They allow, or even encourage, students to use AI tools to assist with monotonous tasks such as skimming articles, fixing code, or conducting preliminary research. Their philosophy seems to be that, as academics, our time is extremely limited, so if there are resources that allow us to save time on routine tasks, why not use them? However, they still discourage students from using AI tools to replace the intellectual labor that reflects their identities as researchers, such as writing or critical analysis.

Then there are professors who welcome AI into their classrooms with open arms. They view the development of AI as a natural technological progression that should be embraced by all, academics included. This does not mean there are no rules; most still implement guidelines around the transparent and ethical use of AI. Some of the guidelines I have seen include citing AI tools used in assignments, submitting the prompts used with AI chatbots, and showing comparisons between AI-generated output and edited versions. These practices allow professors to normalize AI use while also monitoring how students engage with it, helping them learn how to use this emerging tool responsibly.

Each of these approaches has its pros and cons, but it is likely that as students we will encounter all of them during the course of our programs, if not within the same semester. This can lead to what I call “AI codeswitching,” where students must adjust how and to what extent they use AI depending on the classroom context. For students who choose not to use AI, this may not be a concern.

For professors who choose to prohibit AI use in their classrooms, enforcement becomes a major challenge. There are currently no AI detection tools that are fully accurate; I have seen these tools misidentify human writing as AI-generated, and vice versa. Do we then rely on “AI dog whistles”, counting how many dashes a student uses in their writing or scrutinizing their word choices? For social workers, the issue of equity must also remain at the forefront of this discussion. Paid versions of AI tools can produce higher-quality outputs that might more easily evade detection strategies. If we punish students for using AI, how can we be sure we are not simply penalizing those who lack the financial means to afford premium AI tools?

Higher education has a long history of struggling to adapt to change, and AI is no exception. For most universities, it will likely be quite some time before any standard guidelines around AI use are established. In the meantime, as students, we will continue to navigate and balance the differing expectations that professors hold regarding AI.

Navigating Connection and Coping in a Digitally-Driven Academic World

Marsha McDowell (She/her)

Image description: Dark blue background with angular, abstract light blue lines

Navigating Connection and Coping in a Digitally-Driven Academic World

A sense of connection with peers is a cornerstone of college life, helping students manage the stress of academic demands, family obligations, and career planning. This is especially true for graduate and postgraduate students, who often have to juggle multiple responsibilities. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic forced many students to transition to online learning, abruptly disrupting their support networks. The rapid shift to virtual environments introduced not only technological hurdles but also a deep sense of social loneliness for many. Trying to compensate, some students turned to the internet in search of a sense of belonging. However, this often led to new issues, including screen fatigue, burnout, and what is sometimes referred to as “brain rot.”

Now, even as we move forward from the height of the pandemic, reliance on technology persists. Technology enables us to discover community and engage in an ever-expanding market of online education, thereby expanding access and inclusion for students who might have been excluded from traditional academic settings, particularly those from historically marginalized backgrounds. At the same time, studies continue to highlight that prolonged screen time and the pressure to remain "connected" online come with real psychological and physical stressors.

This raises an ongoing challenge: How do we strike a balance between adapting to technology-dependent academic life and managing its accompanying stress? Coping strategies refer to the mental and behavioral methods we use to manage stress, and they play a vital role in our mental health. Research suggests that problem-oriented strategies such as planning, seeking support, gathering information, and reframing stressful situations can improve mental health. In contrast, strategies based on avoidance or excessive use of digital distractions are more likely to worsen anxiety and emotional fatigue.

We are all familiar with the temptation to get lost down an online rabbit hole. While occasional exploration can be enlightening, relying on digital distraction as a primary means of avoiding stress is counterproductive. For instance, as someone who tends to hyper-focus, I’ve found that setting timers and forcing myself to get away from screens is essential. I encourage other students to identify at least one coping method that doesn’t involve technology. While exercise is often recommended, it isn’t accessible or enjoyable for everyone; even simple movement or a change of environment can make a significant difference. Ultimately, students should feel empowered to experiment with different approaches and adapt as their needs change.

Of course, the burden of coping should not fall solely on individuals. The effectiveness of coping is also shaped by the quality of social support and the inclusiveness of a student’s environment. For online learners, this means that institutional leadership, faculty, and peer groups must all be engaged in creating accessible digital spaces, providing up-to-date tools, and ensuring that professors are comfortable and skilled in digital communication. Students who feel emotionally safe and institutionally supported are more likely to thrive, even amid ongoing uncertainty.

However, challenges remain. While many universities are investing in robust virtual platforms and expanded student-centered programs, gaps persist, especially in communication. Not all professors are comfortable interacting digitally, and some even resist email communication altogether, which risks excluding students who rely on non-face-to-face communication. Closing this gap will require ongoing training and a cultural shift in how universities approach digital connections.

As methods of communication continue to evolve, so must our coping strategies and the structures that support them. The future of higher education will be shaped by our collective ability to adapt, prioritize connection, and foster resilient and inclusive communities. By remaining open to new strategies and supporting one another, we can ensure that digital learning environments bolster, rather than undermine, our sense of belonging and well-being.

Our shared progress relies on everyone’s willingness to adapt and grow together.

Tech Burnout and Boundaries: Surviving Always-Online PhD Work

Ruijie Ma (She/Her)

Image depicts a RPM gauge of a car. The numbers and dial are bright white against a black background.

Tech Burnout and Boundaries: Surviving Always-Online PhD Work

In recent years, the work of being a PhD student has become more digital than ever. Many of us spend most of our days in front of screens — teaching online, collecting data, writing, and communicating with advisors and collaborators through email or chat. While technology has made our work faster and more connected, it has also made it much harder to step away. The line between work and rest often disappears.

When Technology Stops Helping

Technology is supposed to make research easier, but for many students it has become a source of stress. Notifications interrupt deep thinking. Online meetings fill up every hour of the day. We feel pressure to respond to messages immediately or risk seeming unprofessional. Over time, this constant connection can lead to exhaustion and emotional fatigue—what many call “tech burnout.”

Tech burnout does not happen all at once; It builds slowly. You might notice that you are tired even after a full night’s sleep or find it feels impossible to focus on one task for long. Some students describe feeling distant from their own work, as if they are completing tasks but not really thinking deeply about them. Others notice that they are more irritable or anxious than before. These are not signs of weakness; they are reminders that our minds need rest to stay creative and thoughtful.

Why Boundaries Matter

In social work, we often talk about professional boundaries as part of ethical practice. The same idea applies to how we use technology. Setting limits is not about being rigid; it is about protecting our time and mental space.

Simple actions can make a real difference. Some students choose to turn off email notifications outside working hours. Others set specific times for checking messages instead of keeping inboxes open all day. A few make sure their work and personal devices are not the same. These habits are small, but they help create a sense of control and predictability.

Boundaries also mean giving ourselves permission to pause. Taking a break in the middle of a writing day or spending one evening completely offline is not wasted time. These moments allow our minds to reset and often lead to more productive work later.

Rethinking Productivity

Many of us grew up in academic cultures that reward constant output. It is easy to believe that success means always being busy or always available. But real progress in research often happens during quiet moments—when we are thinking, reading, or reflecting. Productivity should not be measured only by how much we produce in a week. It should also include how sustainable our work habits are and how well we are taking care of ourselves.

When we start to see rest as part of the research process, not as something separate from it, the pressure to stay online all the time begins to ease. Slowing down does not mean falling behind; It means working in a way that we can sustain over many years.

Collective Responsibility

Preventing burnout is not only an individual task. Departments, advisors, and professional networks like SSWR can all play a role. Faculty can model reasonable email habits and respect boundaries regarding availability. Programs can make space to talk openly about mental health and digital balance. Conferences can encourage asynchronous participation so that students in different time zones do not feel pressured to attend every live event. These are small but meaningful ways to make academic life more humane.

Creating a healthier digital culture requires collective effort. When the people around us value rest and balance, it becomes easier for each of us to do the same. As social work researchers, we already understand how systems shape well-being. We can use that understanding to help shape better systems for ourselves and for the next generation of scholars.

A Final Thought

Technology will remain part of our academic lives. The goal is not to disconnect completely, but to engage with intention. Boundaries are a form of care for our work, our ideas, and our communities. Taking time away from screens is not neglecting responsibility; it is preparing ourselves to return with clarity and purpose.

So, close your laptop when the day is done. Let the silence fill in for a while. The emails, the papers, and the projects will all still be there tomorrow, and you will meet them with a clearer mind.

The Uncertainty of Academic Freedom

Leah Munroe (She/Her)

Image depicts a dark empty hallway in a facility. The walls are bare and darkness of the image obscures he details of the floor.

The Uncertainty of Academic Freedom

Although the job market has always been a worrisome beast for graduating Ph.D. students, it seems to be plagued with a few extra obstacles this year. Several universities have experienced funding cuts or implemented hiring freezes. Additionally, many universities were slow to post job openings, and some have been canceled entirely. The update I did not see coming involved the proposed document from the federal government issued earlier this month to nine universities—including Brown University, Dartmouth College, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Pennsylvania (Penn), University of Arizona, University of Southern California (USC), Vanderbilt University, University of Texas at Austin, and University of Virginia. The proposed “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education” offers preferential federal funding if universities comply with specific policy requirements. These include limits on international student enrollment, tuition freezes, the adoption of standardized testing, and definitions of sex and gender tied to “reproductive function and biological processes.” The document also states that institutions choosing values other than those in the compact would “elect to forego…federal benefits.”

So far, seven of the nine institutions have publicly declined the compact (including Brown, MIT, Dartmouth, Penn, USC, Arizona, and Virginia) while Vanderbilt and the University of Texas have not issued definitive rejections. While this may be the most blatant display of federal policy attempting to shape academic institutions, it is certainly not the first. Earlier this year, universities responded to proposed cuts to federal research and indirect cost funding by instituting hiring freezes, adjusting research budgets, and reducing graduate student intake.

These developments feel especially unsettling as I prepare to enter the job market. The professional landscape already feels uncertain, and the added weight of ideological constraint and financial austerity only intensifies the challenge. Yet social work has always taught us to work within imperfect systems and to hold fast to values of justice and integrity. The same skills we use to navigate complex systems, critical thinking, advocacy, and coalition-building are the ones we will need now to preserve academic integrity and inclusivity.

If universities are to remain spaces of inquiry and imagination, their future depends on the voices willing to challenge constraints rather than yield to them. As new scholars, we inherit not only the uncertainty of this moment but also the opportunity to reimagine what the academy can become: transparent, equitable, and grounded in social justice. The task ahead is not only to find a position, but to help ensure that the values underlying social work continue to have a place within higher education.

references and Further Reading

American Association of Colleges and Universities. (2025, October 3). Statement on the Trump administration’s “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education.” https://www.aacu.org/newsroom/aac-u-statement-on-the-trump-administrations-compact-for-academic-excellence-in-higher-education

American Association of University Professors – Penn. (2025, October 2). Statement by the AAUP-Penn executive committee on the “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education.” https://aaup-penn.org/statement-by-the-aaup-penn-executive-committee-on-the-compact-for-academic-excellence-in-higher-education

Gerhard, D. (2025, February 27). US universities reduce PhD admissions in response to federal funding cuts. The Scientist. https://www.the-scientist.com/us-universities-reduce-phd-admissions-in-response-to-federal-funding-cuts-72734

Mallapaty, S. (2025, March 21). ‘All this is in crisis’: US universities curtail staff and spending as cuts take hold. Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00849-y

Moody, J. (2025, February 19). Federal funding uncertainty prompts hiring freezes. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/government/politics-elections/2025/02/19/federal-funding-uncertainty-prompts-hiring-freezes

Ropes & Gray LLP. (2025, October). White House invites nine universities to enter “Compact” in exchange for access to federal funds. https://www.ropesgray.com/en/insights/alerts/2025/10/white-house-invites-nine-universities-to-enter-compact-in-exchange-for-access-to-federal-funds

U.S. Department of Education. (2025, October 1). Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education. [PDF]. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Compact-for-Academic-Excellence-in-Higher-Education-10.1.pdf

Doctoral Student Spotlight

Image depicts a non-binary person writing in an unlined, cream colored journal at a dark wooden desk. The persons head is out of focus, and only their right arm is visible. The person has tattoos on their right arm and wears a silver ring on their index finger.

Social Work Doctoral Student Accomplishments

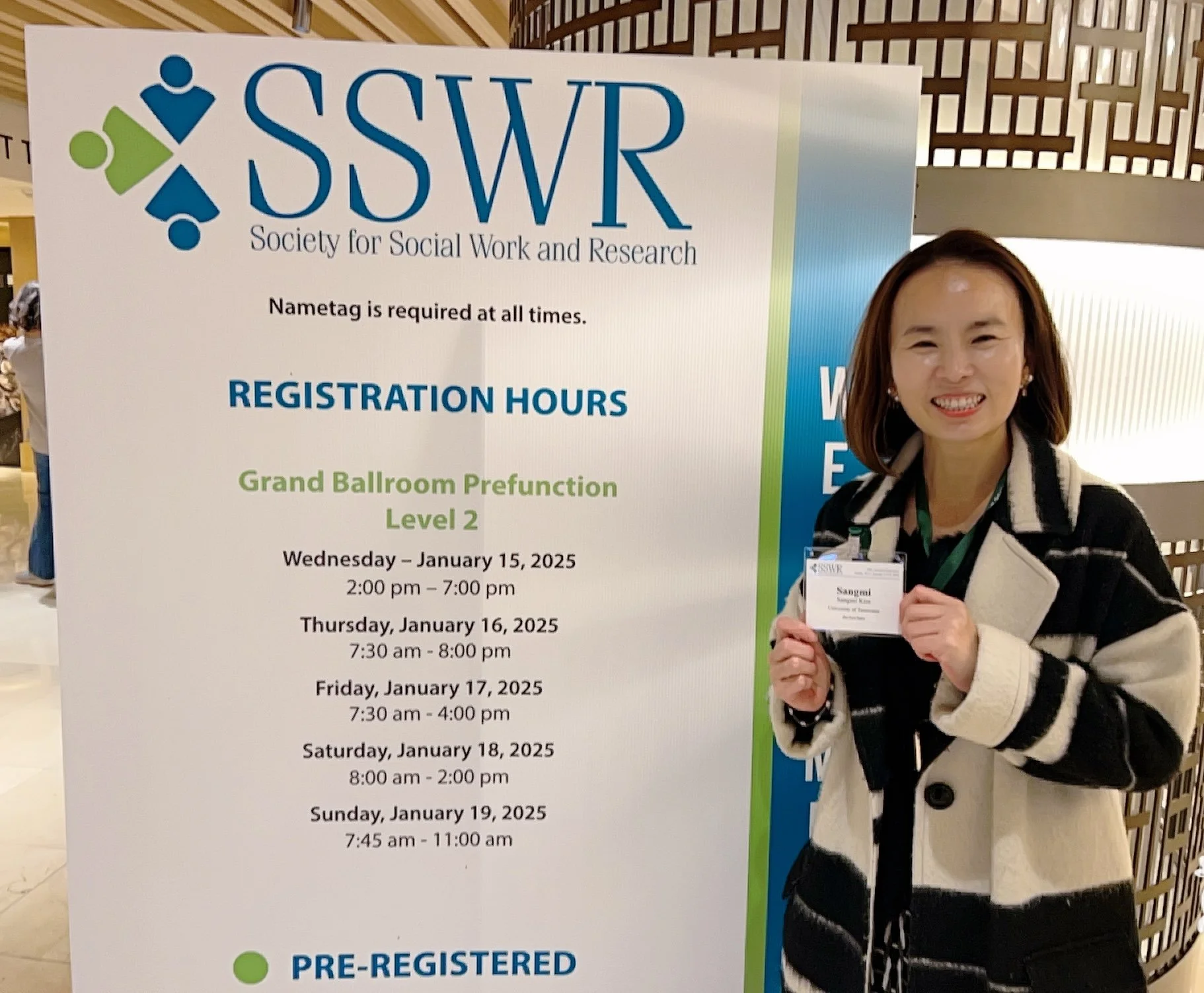

Congratulations Sangmi Kim (she/her)!

Image depicts Sangmi Kim, a Korean woman with straight shoulder-length hair, is smiling and holding her name badge while standing next to a large signboard for the Society for Social Work and Research (SSWR) 2025 Annual Conference. She is wearing a black-and-white patterned coat.

Sangmi Kim received the CSWE Doctoral Student Policy Fellowship 2025–2027, Tennessee Society of Health Care Social Workers Mid East Council Scholarship Award for 2025, and has received funding for her project CBPR-Based AI Digital Storytelling to Address Social Isolation and Prevent Suicide.

Sangmi Kim is a 3rd year PhD candidate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Her research interests include suicide prevention, youth and young adult mental health, data justice, machine learning, and culturally responsive AI tools.

Here’s full information about her awards:

CSWE Doctoral Student Policy Fellowship 2025–2027. (August 2025). Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). Selected as a national CSWE Doctoral Student Policy Fellow, recognizing excellence in social work policy research and commitment to evidence-based advocacy.

TSHCSW Mid East Council Scholarship Award. (September 2025). Tennessee Society of Health Care Social Workers (TSHCSW), Mid East Council. Recognized for academic excellence and contributions to the field of health care social work. Honored at the Annual Ethics Conference 2025.

CBPR-Based AI Digital Storytelling to Address Social Isolation and Prevent Suicide. (October 2024–June 2025). Community Engagement Academy, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Graduate Student Principal Investigator (with Dr. Robert Lucio as faculty advisor). Funded project award: $1,000. In June 2025, I successfully hosted an AI storytelling workshop, and this work was subsequently accepted for presentation:

Sangmi’s recent conference presentations:

Kim, S., Cha, G. E., Won, C. C., Jeong, S., & Lucio, R. (2025, October 1–2). Community-based AI digital storytelling for mental health support: A pilot study for Korean and Korean American adults [Poster presentation]. 8th Annual Engagement and Outreach Conference: Next-Level Engagement—Connect, Collaborate, and Cultivate, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, United States.

Kim, S., Jung, G. S., & Kim, A. (2026, January 14–18). From thoughts to actions: Predicting suicidal ideation and attempts in youth using sex-based machine learning models [E-poster presentation]. 30th Annual Society for Social Work and Research (SSWR) Conference, Marriott Marquis, Washington, DC. In addition to serving as a presenting author, I also collaborated on four additional projects as a contributor.

DSC Call for Nominations: Doctoral Student Achievements

Image depicts several organs and white balloons with gold string in front of a bright blue background. The balloons are emerging from the bottom left corner of the photo.

Submit Nominations for Doctoral Student Achievements!

Celebrate doctoral students’ accomplishments in research, practice, and/or degree milestones!

SSWR DSC Communications Subcommittee has an ongoing call for nominations to showcase social work doctoral student achievements.Nominate a colleague (or yourself) to have their recent accomplishments featured on SSWR DSC social media and in a future DSC newsletter.

The nomination form asks for your name, pronouns, program, a description of the accomplishment(s), information about your research, and brief bio information. If you want, you can also upload a photo of the nominee for us to share and tell us your social media handles to mention in the posts. Student achievements will be posted to social media and the SSWR DSC website as they are received. Achievements will also be featured on the SSWR DSC Newsletter.

View past students showcased for their achievements here.

CLICK HERE TO NOMINATE A COLLEAGUE (OR YOURSELF) TO BE FEATURED

Social Work Snippets

Resources for PhD Students

Research on support in doctoral in programs (Krings et al., 2023)

“Sharing a resource that might be of interest to the DSC and its members. We wrote it with the goal of finding useful and actionable ways to better support doc students” — Amy Krings

Full Citation: Krings, A., Mora, A. S., Bechara, S., Sánchez, C. N., Gutiérrez, L. M., Hawkins, J., & Austic, E. (2023). How Early Social Work Faculty Experienced Support in Their Doctoral Programs. Journal of Social Work Education, 60(2), 206–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2023.2279789

Job Opportunities and Funding

National Dissertation Award for Research on Poverty and Economic Mobility 2025–2026

Deadlines: January 24th, 2025

Postdoctoral Fellowship in Research on Social Determinants of Health & Prevention Science— Virginia Commonwealth University School of Social Work

Deadline: Ongoing

Additional Resources

RESOURCES FOR NEWER CONFERENCE PRESENTERS AND ATTTENDEES

How to Give a Scientific Talk: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-07780-5

Video on How to Confidently Present your Research at Conferences: https://asiaedit.com/webinar/how-to-confidently-present-your-research-at-conferences-in-person-and-online

Not following “SWRnet”?

Formerly known as the IASWR Listserv, SWRnet (Social Work Research Network) was launched in October 2009 to continue serving the social work research community by providing regular updates on funding opportunities, calls for papers, conference deadlines and newly published research. SWRnet is administered by the Boston University School of Social Work.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Disclaimer: This newsletter is created as free service by SSWR Doctoral Student Committee Communications Subcommittee members:

Alauna Reckley (She/Her)

Hannah Boyke (They/Them)

Priyanjali Chakraborty (She/Her)

Julisa Tindall (She/Her)

Shawn McNally (He/Him)

Katie Maureen McCoog (She/Her)

Shani Saxon (She/Her)

Saira Afzal (She/Her)

Leah Munroe (She/Her)

Umaira Khan (She/Her)

Nari Yoo (She/Her)

Emily Joan Lamunu (She/Her)

Dwane James (He/Him)

Seon Kyeong (She/Her)

The opinions expressed in this newsletter are the opinions of the individuals listed above alone and do not claim to represent the opinions of SSWR or the SSWR Doctoral Student Committee